“Operation Titanic”: U.S. turns to satellite technology to detect icebergs

It was the “unsinkable ship” until it wasn’t.

Ten minutes before the maiden voyage of the Titanic ended in calamity, a radio operator aboard the nearby SS Californian signaled that there was an iceberg in the ship’s path. The warning was ignored, and the massive collision that followed cost over 1,500 lives, prompting a wave of maritime innovations: sonar and radar navigation features, lifeboat drills and the creation of the International Ice Patrol (IIP.)

Now, 110 years after the sinking of the Titanic, the U.S. government is developing a new technology that’s designed to detect and report icebergs to the maritime community.

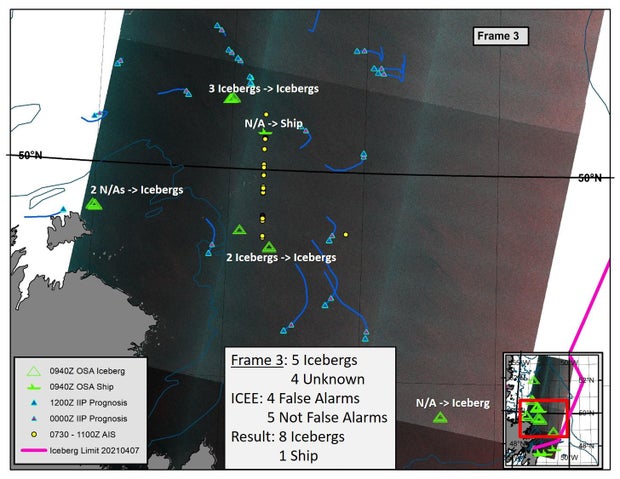

“Operation Titanic,” spearheaded by the Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate, will fuse satellite-based radar imagery with ship reporting systems to enable the U.S. Coast Guard to identify glacial masses throughout the North Atlantic Ocean in real time.

Provided by U.S. Coast Guard

Floating icebergs like the one the Titanic struck on April 15, 1912, still pose navigational hazards today for ships, oil rigs and military assets, says Kathryn Coulter Mitchell, the DHS senior official performing the duties of the under secretary for science and technology, told CBS News.

“The Titanic actually struck the iceberg at a latitude equivalent to the Massachusetts area,” Coulter Mitchell said. “Those of us in this mission space don’t always realize just how far south, how prevalent the iceberg mission is.”

The 16-person IIP is funded by 17 nations bordering the trans-Atlantic, but is operated by the U.S. Coast Guard during ice season, from February through July.

The patrol initially relied on cutters deployed by the U.S. Coast Guard to survey icebergs but switched to aircraft monitoring after World War II. Today, the IIP pilots 9-day aircraft missions every two weeks.

Provided by U.S. Coast Guard

“Operation Titanic” will mark a “complete departure from [U.S. Coast Guard’s] many decades of flying fixed-wing aircrafts to locate icebergs,” said Coast Guard Commander Marcus Hirschberg with the International Ice Patrol. .

Provided by U.S. Coast Guard

“Aerial ice reconnaissance” routinely adds up to more than $10 million in annual costs for the U.S. Coast Guard. Beyond the price tag, C-130J aircrafts that fly bi-weekly missions – roughly 500 aircraft hours per season – are also the U.S. Coast Guard’s most highly sought after aviation assets.

“We’re going to get a lot more bang for our buck once we can use those aircraft hours for disaster response, counterdrug operations, migrant operations and other areas,” Hirschberg added.

The U.S. government has invested $4 million in “Operation Titanic” to date, with money drawn from the Science and Technology Directorate’s Research, Development and Innovation fund.

And while similar technologies are currently used by the U.S. government in rescue missions and flood response, the new satellite technology – which will draw images from the European Space Agency satellites, U.S. commercial providers and Canada’s RADARSAT Constellation – will be the first of its kind to access global satellite data.

The satellite-based radar imagery remains fully operational in dark, overcast conditions that often prevent normal aircraft operations. Hirschberg called it a “game-changer for forecasting the season.”

“When the Coast Guard came to us with this, the hope was to overcome the challenges with [technology] that is immune to darkness and overcast, so we can see further upstream of the transatlantic shipping lines than we ever have been before to issue longer-term predictions,” Coulter Mitchell said.

“For forecasting, we’re looking at icebergs that are way far North that we can’t reach with aircrafts, even flying from St. John’s Newfoundland,” said Hirschberg.

“A lot of times there’s a mechanical issue with the plane, inclement weather, or we can’t get the hangar door open because of high winds. So we do lose a lot of opportunities to fly,” he added.

Glaciers in parts of the North Atlantic are melting so quickly that changes can be viewed from space. The latest “Arctic Report Card,” published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), found the region warms twice as fast as the rest of the Earth, resulting in the rapid loss of ice cover.

“We see so much season-to-season variability,” Hirschberg told CBS News. “In 2019, we had 1,500 icebergs pass south of 48° North latitude – about where the Titanic sank. In 2020, we had a single iceberg pass that limit.”

U.S. Coast Guard officials anticipate using satellite images will help the branch navigate changes brought on by a transforming climate.

The International Ice Patrol is slated to test-run “Operation Iceberg” for two years, beginning in 2023 before launching the program.